Good Saturday we attended the Deer Dance on Pascua Yaqui land. The Deer Dance blends Yoeme tradition with later Catholic influence. Both Yoeme (Yaqui) and Spanish recognized the parallels: weeks of austerity to prepare for the climax of temporary death (the Deer or Jesus) followed by resurrection and salvation. It is a form of spring festival in which the Deer Dance on Good Saturday is a major event. The first Spanish who encountered the Yoeme and named them Yaqui also named them Pascua Yaqui (Easter Yaqui). Spanish Padres incorporated the Yoeme festival into the Easter calendar. The dancing is still done today, in an open sacred space in front of the Chapel of Christ the King in Pascua village.

The Pascua Yaqui Reservation is small. The Pascua village is just south of Tucson and abuts the northern boundary of the much larger Tohono O’odham Reservation. We drove by the imposingly large but neat Casino del Sol, proceeded a few blocks past nicely neat civic buildings, and parked in the spaciously wide and dusty street.

The sacred space was a long rectangle of flat, dusty earth, almost a hundred yards long and twenty wide. Both sides were marked with sprigs of fresh cottonwood (I think) leaves pushed into the hard ground. Framing the sides of the broad public space around the sacred space, were long, continuous stalls that sold mostly drinks and food.

The stalls were painted white and the Pascua vendors hadn’t bothered with signs, Pepsi, Coca-Cola or otherwise. Their plainness matched the tones of the pink earth and the whitewashed church. The simplicity was also reflected by the strict and oft-repeated prohibition: no pictures, no cell phones. To try to use one would have resulted in immediate confiscation and destruction. Pascua Yaqui law was enforced by Pascua Yaqui police, crowd ushers, and pretty much everyone else there. “Take pictures in your mind, your heart, your body,” repeated the friendly voice of the bi-lingual announcer. Also strictly prohibited were alcohol, drugs, and drawing (for those who wanted to sketch the scenes instead of photographing them).

Simple also was the seating. I don’t believe I’ve ever seen so many folding camping chairs in one place. They were three and four deep on both sides. There must have been a thousand people there, mostly local, plus about one or two hundred directly involved in the ceremony. The local population is only four thousand.

Ceremony. Dance. Ritual. Festival. Pageant. There is no one good name that describes the wonder that we witnessed. It has roots in the origins of who we are and the Yoeme belief that the ritual dance helps maintain the balance of good in creation. It was also family-friendly, all in one. And what we saw was only a tiny part of the whole that unfolds over weeks. The dancers we saw had been dancing for days and weeks.

The Pascua don’t talk about it. Like no photographs, they prefer the direct experience. Even those who work for the tribe don’t get explanations. Our connection to the experience, let's call him "Bob" to protect his identity, told us that when he would ask the meaning of some part of the event, he would get the response, "I would have to ask grandfather." It was a polite brush-off. Still, Bob had pieced together some of what happens, and there is enough scattered on the internet to shed some more light.

What I saw was long formations of men and some young teenagers dressed in black with purple or red trim, brandishing what looked like wooden swords painted black with red and white details. Most had black cloth around their heads and hats, covering their faces. All wore simple leather sandals and many puttee-like leg wraps, their feet stepping, stamping and shuffling in unison to the beats of wooden knives on wooden swords. All had crosses on their black robes; a protection for the dancers, just in case. These were the Chapayekas, the demons or otherwise bad spirits. Converted to Christianity in the 17th Century, the Chapayekas of the Yeome became identified as the common soldiers of the Fariseos, masked characters wearing elaborate costumes with fantastic, sometimes grotesque shapes. Some Fariseos looked like pink skinned, bearded Anglos. One of them had a top hat and carried a book. Others looked like a clown or a contorted pig. They were the Pharisees.

What I saw was long formations of men and some young teenagers dressed in black with purple or red trim, brandishing what looked like wooden swords painted black with red and white details. Most had black cloth around their heads and hats, covering their faces. All wore simple leather sandals and many puttee-like leg wraps, their feet stepping, stamping and shuffling in unison to the beats of wooden knives on wooden swords. All had crosses on their black robes; a protection for the dancers, just in case. These were the Chapayekas, the demons or otherwise bad spirits. Converted to Christianity in the 17th Century, the Chapayekas of the Yeome became identified as the common soldiers of the Fariseos, masked characters wearing elaborate costumes with fantastic, sometimes grotesque shapes. Some Fariseos looked like pink skinned, bearded Anglos. One of them had a top hat and carried a book. Others looked like a clown or a contorted pig. They were the Pharisees.When we arrived around ten in the sunny morning, a donkey had been hanging around the front of the church with its young cowboy rider. Over an hour later, as the procession of Chapayekas entered the space, the donkey had become the bearer of the idol worshiped by the demons. The idol was Judas, an effigy figure of a man held up on the donkey on either side by a man with a stick. The procession was accompanied by the rhythmic clicks of wooden daggers and swords and the sound of scores and scores of sandals shuffling in unison on the ground, slowly and energetically.

Slowly the black robed Chapayekas and magnificently hideous Fariseos paraded down one side of the space, but only as far as a broad white line of chalk in front of the church, than back the other side. The lines of dancers continued outside the space and disappeared. Bob told us they proceeded around the town. They were the bad guys proudly parading Judas because Jesus had been killed the day before, on Good Friday.

The Lenten activities of the Pascua Yaqui are organized by societies. Some are the singers and chanters, others perform the role of Chapayekas and Fariseos, and there is, of course, the Deer Dancer Society. After the initial parade, some of the Chapayeka and Fariseo participants returned with gourd bowls to collect donations from the audience.

Sometime later (we were on local time, which passes on its own schedule) we spotted the Deer Dancer getting ready in the space in front of the church protected by the white line. With him were older men dressed in colorful and glittering cloths. They were angels. They all wore rattling shells on their legs.

Gently, timidly, the Deer Dancer began to dance, moving like a nervous deer looking to graze.

In front of the church were lots of folks, regular folks; the faithful, if you will, who also played in this Easter Deer Pageant. They had a big canvass full of fresh greens. The Deer Dancer timidly danced towards the canvass, then partook of the greens that were offered.

The Chapayekas and Fariseos returned, always staying back from the line protecting the church, the Deer, angels and congregation on the church side. A bad guy dressed as a hunter came forward to the line and shoots several arrows at the Deer and seemingly killed it. Then demons and archer rhythmically paraded back out. The Deer somehow just got up. (I didn’t quite get an understanding of that part because I thought resurrection would be more dramatic.)

All this time the audience was behind the cottonwood sprig-demarked lines on either side of the sacred space. Scores of minutes passed. The crowd got bigger. It seemed as if everyone was drinking sugar drinks and eating tacos, fried chips, ketchup, and Navaho fried bread purchased from the food and drink stalls. The locals mostly carried on as if at an extended family picnic, iced coolers, camp chairs, fidgety kids, and all. From snippets of conversation, it was obvious that many were related or knew one or the other hooded or masked participant.

All this time the audience was behind the cottonwood sprig-demarked lines on either side of the sacred space. Scores of minutes passed. The crowd got bigger. It seemed as if everyone was drinking sugar drinks and eating tacos, fried chips, ketchup, and Navaho fried bread purchased from the food and drink stalls. The locals mostly carried on as if at an extended family picnic, iced coolers, camp chairs, fidgety kids, and all. From snippets of conversation, it was obvious that many were related or knew one or the other hooded or masked participant.The announcer advised that the celebration was about to begin, but tens more minutes passed as the participants prepared. Meanwhile, those in the crowd armed themselves with baggies full of homemade confetti.

The demons returned. I don’t know what happened to the idol on the donkey, but some forty minutes later, the fate of the idol became obvious.

The columns of black demons led by the masked ghouls paraded, more like danced, two-thirds into the space to the beat of sticks and the shuffle of feet. They slowed, almost to a stop. The angels by the Deer were shouting at them, perhaps taunting the demons. They were joined by the congregation. Finally, the demons had enough.

The lead Chapayekas gave the signal and the demons rushed the white chalk line with a shout. Pandemonium broke out. Yells, shouting, sticks on sticks, firecrackers, blank shots from pistols, and exceedingly powerful explosions of firecrackers, all accompanied by the audience throwing confetti.

(Originally, the confetti would have been flowers. Yaquis consider flowers as one of the four worlds, the others being animals, people, and the dead. Significantly, the Deer Dancer’s antlers are decorated with flowers.)

Three times this happened. Each time the formation of ghouls and demons approached to a different and increasingly faster beat of sticks and shuffle of feet. Each time the demons paused, the angels taunted, the deer grazed, and then the attack. Each rush was a din of mock fighting, drums, shouts, firecrackers, blank shells, and sudden explosions so loud that the body vibrated. Each time the demons were repulsed at the line.

After the second unsuccessful attack, some of the folks in front of the church ran across the line to the far end of the space where the demons had retreated. There the they took the black robes and masks of some of the demon group. After the third change, all the demons had taken off their black robes, dropped their wooden swords and knives, and rushed into the church.

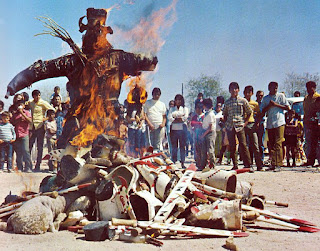

Bob explained that the demons had been converted. Their wooden swords, masks and idols were burned in a big bonfire. Indeed, I had noticed stacks of mesquite firewood and the Pascua Yaqui Fire Department trucks positioning themselves on the street on the very far side of the space. As the audience dispersed and we left after the mass salvation, we could see the smouldering frame of the Judas effigy and pieces of painted wooden swords still burning in an intensely fierce fire.

The participants had entered inside the church where, in another part of the ceremony that is private to the participants, Bob explained, those who had played the roles of Chapayekas and Fariseos received blessings and absolution.

The Deer is not Christ literally. The Deer and what we experienced have a much deeper meaning.

No comments:

Post a Comment